My struggle with Arabic began in October 2012, with a couple of false starts. I tried initially to find a private tutor for Egyptian Arabic but found instead a morose Palestinian girl with no teaching experience or qualifications, who insisted we should meet in a noisy café where she proposed to teach me. I refrained from meeting her again. I then paid £50 for an adult education course in the public library. I should say straight away that this sum was refunded to me in full after I described the “lesson” to the organisers. After that, I decided to sign up for a course at the university language centre. Although I knew by now that I was not going to get Egyptian Arabic, the third teacher at least turned out to be a real teacher.

Prior and subsequent experience has taught me that real Arabic teachers are in the range of extremely rare to non-existent. I have also learnt that language teaching methodology is not one size fits all. I could not possibly have learnt Arabic the way I might learn Spanish. (Spoiler: Arabic has a different alphabet and belongs to a different language family from Spanish and English). Communicative language teaching methodology requires the teacher to speak only in the language s/he is teaching. I call it the ‘shout a little louder’ school of teaching; it appears to be based on English speakers not being able to speak any other languages. I have found that if someone speaks slowly and clearly to me in grammatical Spanish, I can learn something (although I’d probably learn less if I didn’t know Latin and French). The problem is, the bigger the language gap, the less likely this method is to work.

Picture this: an Arabic teacher comes into a classroom of complete beginners, all of them speakers of European languages only. S/he speaks in Arabic (which isn’t Indo-European, obviously) and decorates the whiteboard with unintelligible squiggles. Time allowed: 100 years, and counting. But now let’s say that some of the students have some very rudimentary Arabic (though not the alphabet). They try to say the things they know. The teacher instantly and categorically rejects every single one of these utterances because they are not Modern Standard Arabic, a made-up ‘high’ version of the language comparable to Katharevousa, the ‘purifying’ language that used to be mandated for education, journalism, and all other state functions in Greece. Like Katharevousa, Modern Standard Arabic is not a real vernacular, and most people cannot use it to communicate.

My father’s first language (of several) is Egyptian Arabic, or ‘dialect’ as most Arabic teachers insist on calling it. It’s not a dialect unless you think American is a dialect of English. Curiously, my mother’s first language really was a form of dialect: Dorset. She learnt to ‘talk posh’ (or at least middle class) at college, no mean linguistic feat. So, both my parents, in a sense, spoke English as a foreign language. Or did they? My father started school at the age of three in French and switched to English school when he was about ten. The rest of his education was in English. He read medicine in Alexandria; medical school in Egypt is entirely in English (although one university in the south offers the programme in French). At school, my father found French and English much easier than “Arabic”, the grammatically tortuous high version of the language that he and his contemporaries were forced to study but did not speak. If you want to read and write in Arabic, of course, you do need to be able to deal with MSA.

My father’s first language (of several) is Egyptian Arabic, or ‘dialect’ as most Arabic teachers insist on calling it. It’s not a dialect unless you think American is a dialect of English. Curiously, my mother’s first language really was a form of dialect: Dorset. She learnt to ‘talk posh’ (or at least middle class) at college, no mean linguistic feat. So, both my parents, in a sense, spoke English as a foreign language. Or did they? My father started school at the age of three in French and switched to English school when he was about ten. The rest of his education was in English. He read medicine in Alexandria; medical school in Egypt is entirely in English (although one university in the south offers the programme in French). At school, my father found French and English much easier than “Arabic”, the grammatically tortuous high version of the language that he and his contemporaries were forced to study but did not speak. If you want to read and write in Arabic, of course, you do need to be able to deal with MSA.

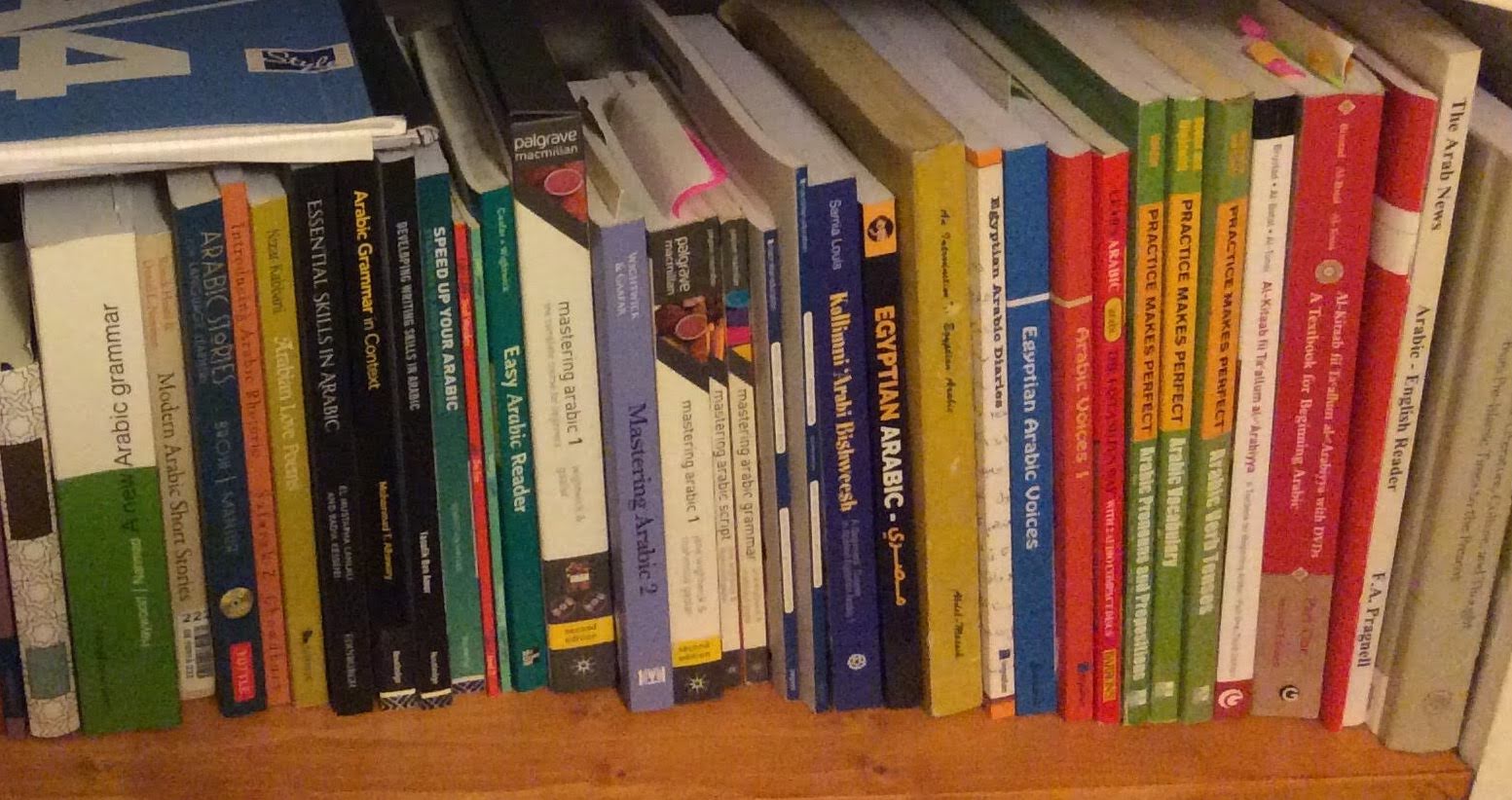

And so to class. Yousif is an amazing teacher but the standard book we were asked to buy (at vast expensive), ‘Al Kitaab’, is a nightmare. Supposedly for beginners, the very first vocabulary items in unit 1 are ‘Literature’ and ‘The United Nations’. Why? I have never seen a beginner’s book like this; it is a horror show. A Dutch professor of Arabic, the sister of a friend of mine, recommended another book, ‘Arabic for Life’. It was a godsend. I also worked my way through ‘Mastering Arabic’ and then the ‘Easy Arabic Reader’, which I came to know as ‘Terminally Boring Jamal’. Inspired by the excellent ‘Spanish Verb Tenses’, I acquired ‘Arabic Verb Tenses’, and worked my way through that and also ‘Arabic Pronouns and Prepositions’. I did four years (which included repeating Year 2 at my own insistence) at the language centre with a year off in-between, during which I continued to study solo and with various private tutors. The two best ones were friends: Sayeed and Simon. Sayeed was a beautiful young Syrian musician. He moved to London to pursue his music and died suddenly of a rare heart condition (diagnosed too late). Simon is a very gifted Arabic student, who got a scholarship to do a Ph.D. and also moved away. They were only briefly available to give lessons but were both marvellous. I was readmitted to Year 3 at the language centre and completed it (and passed the end-of-year exams), but Yousif was then accepted for a D. Phil and so he, too, stopped teaching. Some of us tried Year 4 with the new teacher but she was absolutely hopeless, ranting at us in dreadful English about not needing to learn the rules of grammar. If I had been her English teacher, I would certainly have tried to disabuse her of this absurd belief. The new “Intermediate” class turned out to be mixed-level and included fluent Arabic speakers; we complained and voted with our feet.

At this point, I decided I had had enough of MSA and only wanted Egyptian. I started buying books with ‘Egyptian Arabic’ in the titles. None had been available when I first started. And this is how I came across the Lingualism publications. They are a revelation. I began by working through ‘Egyptian Arabic Voices’, marvelling at the fact that here at last was an Arabic book produced by someone who knew something about language teaching and learning. In common with the other Lingualism books, this one makes sense, contains useful language information, uses proper grammatical terms, and provides structured, intelligent exercises.

Before giving a few details of the other Egyptian Arabic books produced by Lingualism, I would like to say something about two bizarre books from other publishers that purport to teach Egyptian Arabic. The first has no real academic pretensions and is billed as a dictionary and phrasebook with cultural information. It was published in 2013, and here is an example of the ‘cultural information’ it contains: “Broadly speaking, Egyptians have an agreeable dusky skin colour. […] Their eyes tend to be brown and expressive and facial hair is quite common among men”. The authors, Gaafar and Wightwick, (who are also responsible for the ‘Mastering Arabic’ series and Terminally Boring Jamal) go on to explain that affection between friends in Egypt does not indicate homosexuality (p.186). In fairness, their introductions to Modern Standard Arabic grammar (‘Mastering Arabic Grammar’) and script (‘Mastering Arabic Script’) are useful, although the examples, short passages, and exercises in the ‘Mastering Arabic’ series are as boring as hell.

The second Egyptian Arabic book from elsewhere bears the title ‘Keda Mazbout’ and is the work of Mona Kamel Hassan of the American University in Cairo (AUC, 2020). The transliterated title is the first problem (the Arabic version isn’t even given). The way the first word is written, ‘keda’, would lead an English speaker to believe that it should be pronounced ‘kedda’ (to rhyme with Cheddar) or possibly ‘Kee-dah’ (as in Lah-dee-dah). I can’t imagine anyone inferring from this off-beam transliteration the correct pronunciation: ‘Kidda’. Worse, the phrase is nowhere explained in the book! (It means ‘That’s right’). This book is characterised by extremely strange grammatical ‘explanations’ and mind-blowingly tedious language exercises, mostly drills, without a single answer key. I think the poor learner is somehow intended to memorize the pages (and pages) of rules, some considerably more important than others.

In contrast, the books from Lingualism produced by Matthew Aldrich and his co-writers are exactly what this learner had been waiting for, increasingly despairingly. Although the sight and title of the large-format ‘Big Fat Book of Egyptian Arabic Verbs’ (2016) provokes a certain amount of hilarity from friends who see it on my bookshelf, this is an amazing work of reference. The examples in it are incredibly inventive as well as relevant. When you are struggling to learn a language (and that includes learning to read in your own language as a child), the last thing you want is to be confronted with boring rubbish that simply isn’t worth the effort of understanding. Children need something a lot more engaging than ‘Peter and Jane’ or ‘Ant and Bee’, those outdated ‘reading books’ that were never in date in the first place. If I had never learnt to read, Ant and Bee would have had a large share in the responsibility. It is hard to think of two more desperately demotivating characters – unless, perhaps, Terminally Boring Jamal.

‘Talk Like an Egyptian’ (Lingualism, 2021) is fun; ‘Egyptian Colloquial Arabic Vocabulary’ (Lingualism, revised edition, 2020) is very useful, and ‘Shuwayya ‘An Nafsi’ (‘A Little About Myself’; Lingualism 2016) is helping me to piece together my own sentences because the conversations in it are extemporised (in answer to sensible questions) by real people and the text is broken down lexically and grammatically, with every single vocabulary item glossed every time it comes up. This means that you don’t have to go through the units in the published order if you don’t want to. It is also usefully cross-referenced to the Vocabulary book. ‘The News in Egyptian Arabic’ (Lingualism 2020) is fantastic – right up to date and jam-packed with fascinating stories, relevant vocabulary, and useful language exercises

I have struggled with the accompanying audio material, partly because I kept getting locked out of the website – probably my own fault because I kept forgetting my user ID and password – and partly because some of it is just too fast for me. One morning, I got so frustrated that I sent an ill-tempered e-mail to Lingualism. Within a couple of hours, I received the most charming and helpful response imaginable, proposing solutions and wishing me ‘a better day’. And that is how I had the good fortune to ‘meet’ Matthew and concluded I would like to write this blog. Matthew and Lingualism have definitely given me a great many better days in my Arabic-learning journey.