I began studying Arabic in 1999. Before embarking on this long and unending adventure, I studied the Philology of Romance Languages. At university, I was introduced to the concepts of “substrate” and “superstratum.” Roughly speaking, we can consider the first as the lexical (and even syntactic) primary heritage of a language. The superstratum (which is itself a substrate) is a language that is spoken by a dominant group that eventually exerts a strong influence on the language(s) spoken by other peoples.

Within the Romance languages, the Latin superstratum was somehow imposed on Gauls, Celtiberians, and Tuscans. The result of this is the modern languages of French, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, and Italian.

I believe that Latin was never spoken in the form of classical texts. Instead, it crystallized religious doctrines, codes of law, philosophical opinions, and scientific principles. Nevertheless, the texts have a complex construction system, combined with a very flexible syntax, which makes reading a complex endeavor. When reading Latin texts, at least for Portuguese speakers, it is necessary to do in-depth linguistic analysis as well as an “archeology of the phrases.”

The recondite configuration of Latin phrases helped me understand why Romanesque peoples were only partially and heterogeneously Latinized. Otherwise, how can we expect people with different linguistic backgrounds to uniformly speak a language that came to them as the source of legal, moral, and religious norms? Due to the low literacy level 1,500 years ago, classical Latin was handled by a few skilled readers and even fewer able writers.

As a result, peoples were able to absorb the Latin language throughout the Latin world through the use of a simpler variation (vulgar Latin), which remained for more than a millennium the “lingua franca.” The fusion of this “vulgar Latin” with substrates spoken in the respective domestic environments of each region or country created the Romance languages are characterized by:

- a simplification of the Latin case system

- a more stable phrasal order under the pattern “Subject-Verb-Object”

Why am I focusing on Latin and Romance Languages so much? This can help us better understand what is meant by “the Arabic language.” What is meant here is not solely a language or a dialect, but rather a family of languages currently emerging under the umbrella of classical Arabic.

The Arabic and Romance languages are not just derivations of a standard version, but the result of the contact of earlier substrates with the classical Arabic superstratum, which resulted in a unique development of each “dialect,” subject to later influences.

Thus, on the whole, we can compare classical Latin with the Arabic of classical times; we can compare vulgar Latin with the Modern Standard Arabic (MSA); we can view each Romance language as similar to a national dialect. Another point of comparison is that classical Arabic, with its elaborate orthographic and grammatical rules, is giving way to MSA, and even this is not spoken every day spontaneously.

In addition to the phonetic and sociolinguistic differences between MSA and each colloquial variant, there are stylistic, lexical, and syntactical differences as well. There are also differences between each colloquial variant, and even MSA may not be spoken uniformly throughout the Arabic world.

If we compare each of the national dialects of Arabic to a Romance language, we can understand the difficulty of mutual understanding. So, the Iraqi dialect could take the place of Romanian, while the Hassania (Mauritanian) dialect, at the westernmost extreme, would be the equivalent of Brazilian Portuguese.

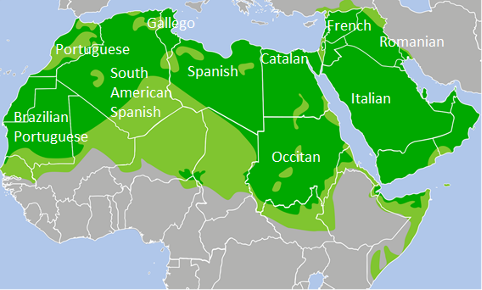

As a better visualization, the linguistic map of the Neo-Latin world can be overlayed on the map of Arab countries as follows:

As in the Romanesque world, some variants are more central, while others are more peripheral. For example, the Moroccan “darija” has Iberian and French elements that make it farther from the Arab core, just as Romanian is more disconnected from its western siblings for its Slavic and Turkish lexical and phonetic elements.

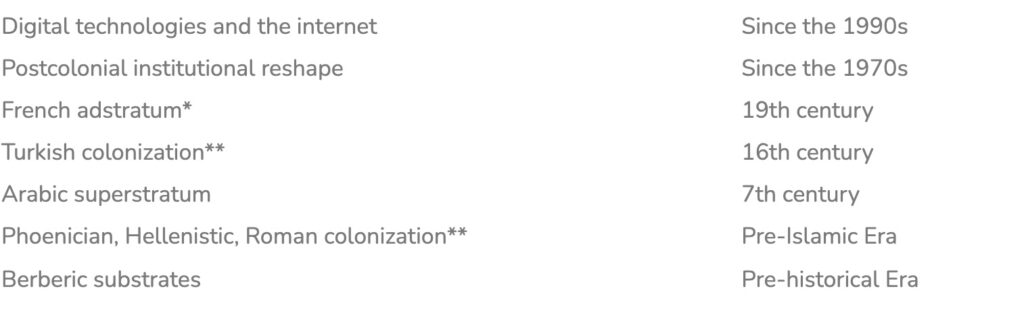

Let us take a look at the historical stages that explain the particular heritage of the contemporary Algerian dialect:

Digital technologies and the internet | Since the 1990s |

Postcolonial institutional reshape | Since the 1970s |

French adstratum* | 19th century |

Turkish colonization** | 16th century |

Arabic superstratum | 7th century |

Phoenician, Hellenistic, Roman colonization** | Pre-Islamic Era |

Berberic substrates | Pre-historical Era |

* similar to a substrate **lesser linguistic influences

These stages are like geological layers underlying each dialect in an oversimplified view. But unlike geology, the current dialectal manifestations are a blend of historical, political, economic, and cultural influences, particularly the ones that are happening now.

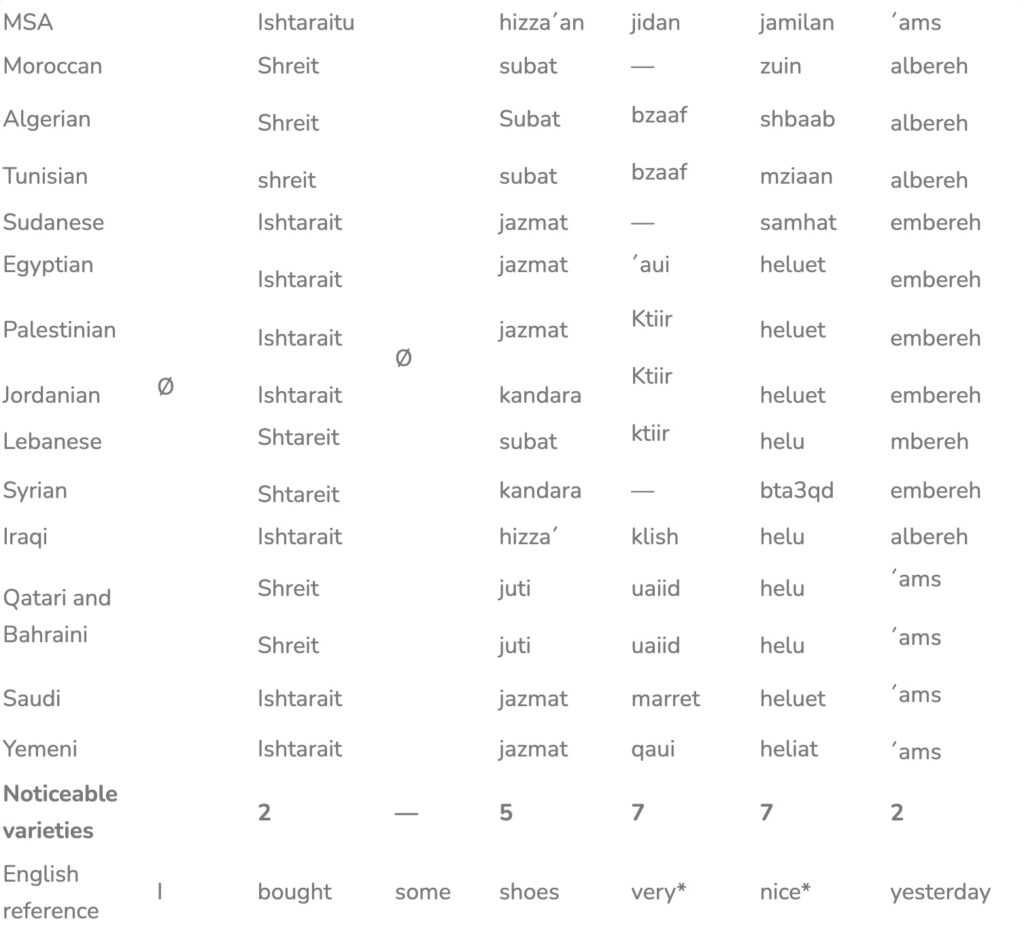

Now that that has been said, let us compare Arabic and Romance in general. The following example is taken from page 3 of the book “Arabic vs. Arabic: a Dialect Sampler” by Mathew Aldrich to show how the English sentence “I bought some very nice shoes yesterday.” can be composed in both Romance and Arabic languages. There are at least 15 ways to say it in Arabic:

The table below presents the sentence with Latinized spelling, separated by paradigmatic items:

MSA | Ø | Ishtaraitu | Ø

| hizza´an | jidan | jamilan | ´ams |

Moroccan | Shreit Shreit shreit | subat | — | zuin | albereh albereh albereh | ||

Algerian | Subat | bzaaf bzaaf | shbaab | ||||

Tunisian | subat | mziaan | |||||

Sudanese | Ishtarait Ishtarait Ishtarait Ishtarait | jazmat | — | samhat | embereh embereh embereh embereh | ||

Egyptian | jazmat | ´aui | heluet | ||||

Palestinian | jazmat | Ktiir Ktiir ktiir | heluet | ||||

Jordanian | kandara | heluet | |||||

Lebanese | Shtareit Shtareit | subat | helu | mbereh | |||

Syrian | kandara | — | bta3qd | embereh | |||

Iraqi | Ishtarait | hizza´ | klish | helu | albereh | ||

Qatari and Bahraini | Shreit Shreit | juti juti | uaiid uaiid | helu helu | ´ams ´ams ´ams ´ams | ||

Saudi | Ishtarait | jazmat | marret | heluet | |||

Yemeni | Ishtarait | jazmat | qaui | heliat | |||

Noticeable varieties | 2 | — | 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 | |

English reference | I | bought | some | shoes | very* | nice* | yesterday |

*modified sentence order to allow lexical comparisons

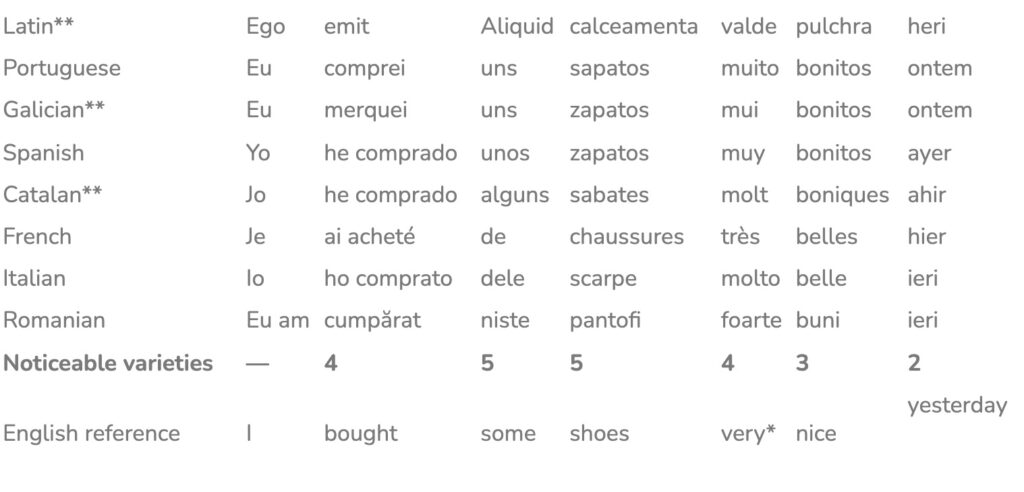

I now want to do the following exercise in living Romance languages:

Latin** | Ego | emit | Aliquid | calceamenta | valde | pulchra | heri |

Portuguese | Eu | comprei | uns | sapatos | muito | bonitos | ontem |

Galician** | Eu | merquei | uns | zapatos | mui | bonitos | ontem |

Spanish | Yo | he comprado | unos | zapatos | muy | bonitos | ayer |

Catalan** | Jo | he comprado | alguns | sabates | molt | boniques | ahir |

French | Je | ai acheté | de | chaussures | très | belles | hier |

Italian | Io | ho comprato | dele | scarpe | molto | belle | ieri |

Romanian | Eu am | cumpărat | niste | pantofi | foarte | buni | ieri |

Noticeable varieties | — | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

English reference | I | bought | some | shoes | very* | nice | yesterday |

*modified sentence order **obtained from Google Translator

Among Romance languages, certain items are less diverse lexically, and there is more rigidity in the syntax. Conversely, colloquial Arabic departs from the “Verb-Subject-Object” pattern of classical Arabic.

The rifts between sibling languages are becoming wider over time, leaving us with “skeletons,” “dry cocoons,” or “idealistic examples” that allow comparisons and general understandings but below the living reality of creation and transgression.

Others have stated (such as Reem Bassiouney, in Arabic Sociolinguistics, Edimburg University Press, 2009) that the differences between the “Arabic languages” are akin to the differences between “Romance languages.”

However, Latin had a stronger influence over people colonized by Rome for at least seven centuries longer than Standard Arabic had over Arabized countries. Thus, the transformations and tensions between the classical language and the variants occur in different material, technological, social, and educational contexts.

Religion, armies, or laws are not the primary sources of standard languages, but rather the media.

In the Latin world, the press contributed to the nationalization of certain dialects and consolidation of orthographic and grammatical standards since the 16th century. It was only later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, under the Ottoman empire, that Arab lands were subjected to this phenomenon, mostly in Syria and Egypt. It was in this context that colloquial dialects and unwritten dialects flourished alongside MSA. Radio, film, and television helped spread Egyptian and Lebanese dialects and oral MSA during the 20th century.

Standard Arabic is not imposed in all situations, but it is used during religious readings, school instruction, and academic and bureaucratic activities. Therefore, it can be seen as the “lingua franca” of the Arab peoples, while the dialects represent the codes of intimacy and nationality.

Colloquial communication deviates from the standard because of simplifications, a lack of verbal flexions and declensions, word fusions, etc., to save time and energy, as well as a limited number of phonemes that are necessary to understand the spoken word.

Formal spoken Arabic is more like a written message read aloud. The spoken news usually consists of a series of denotative and grammatically correct sentences, but with some pauses, gaps, or improvised lines over text that has been written beforehand.

When listening to oral discussions or watching more relaxed television shows, we witness some speakers using diglossia, injecting colloquial constructions into the Classical Arabic structure, or mixing colloquial speech with fragments of literary language.

The formal and colloquial dimensions do not live in total apartheid, and now we see the internet bringing new “standardizations” of the colloquial language and “colloquializations” of MSA, whether by the traditional media institutions, whether by Youtube and other platforms, where creators make unprecedented mixes of colloquial and literate usages.

Because of its absence of visual context, written text requires more precision and fidelity to the standard, but is still open to creative transformation, as in poetry, literature, or theoretical innovation. Many works of literature in the Arab world bring different and interesting blends of dialects and MSA, which is reflective of the national patterns and styles.

For my conclusion, I would like to reiterate the idea that the Latin world provides a good key to understanding the pulsating events taking place in the Arabic world, a truly open-air laboratory, for someone to wonder how things happened within the Latin world. All of this takes place in highly innovative circumstances, in which TV and the internet are just two examples, accelerating and producing many manifestations of “standardization” and “differentiation” entwined over the long term.

Very interesting article, thank you!